Our Legacy:

447 Years of Enduring Love

Love beyond the Wall, Promoting Dignity

Against Exclusion, Neglect, Discrimination, and Poverty.

Our Franciscan Founder:

Brother Juan Clemente

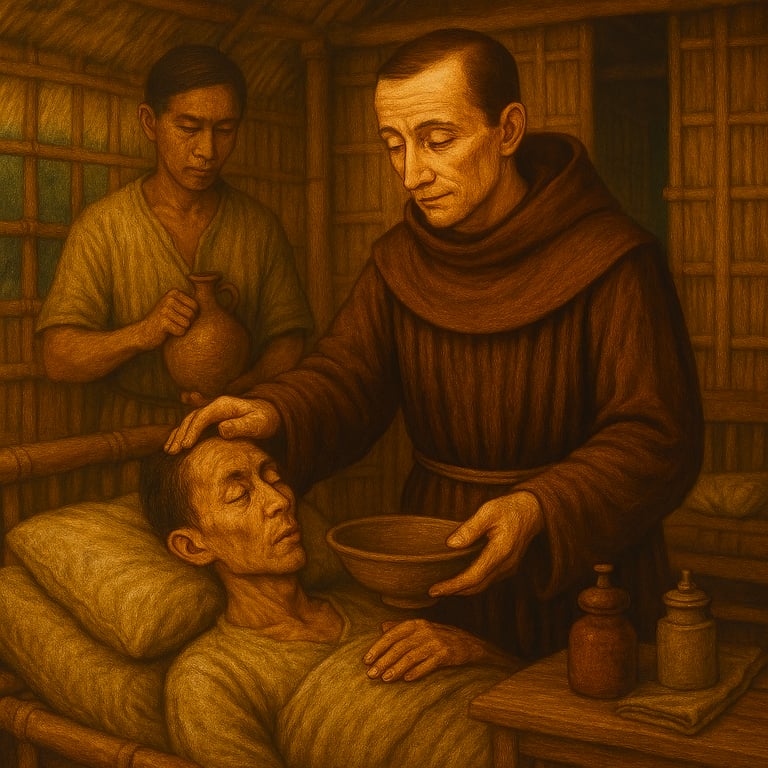

In 1578, Fray Juan Clemente—a humble Franciscan friar from Mexico—was moved by the silent suffering of those cast aside by society. Beyond the walls of Intramuros, he saw not neglect, but a calling: to serve the sick, the poor, and the forgotten.

With little more than nipa and mercy, he built a modest ambulatory dispensary near the Franciscan convent. There, Manila’s indigent found herbal remedies, palliative care, and spiritual comfort. Though simple in form, the ward radiated the Franciscan ideals of poverty, compassion, and loving service. It became a sanctuary of healing—where dignity was restored and hope rekindled.

Fray Juan Clemente was not only a spiritual founder, but a practical visionary. He gathered alms, recruited helpers, and secured support from colonial authorities. His tireless efforts laid the foundation for two enduring pillars of Philippine healthcare:

San Juan de Dios Hospital, dedicated to those in need of medical care

San Lazaro Hospital, devoted to the care of those afflicted with leprosy

His legacy is not merely historical—it is a living testament to love that endures, heals, and uplifts.

AI-Generated Portrait of Fray Juan Clemente, OFM

AI-Generated Image of Fray Juan Clemente

AI-Generated Image of Fray Juan Clemente

The Hospitaller Brothers:

A Legacy of Hospitality and Healing Care

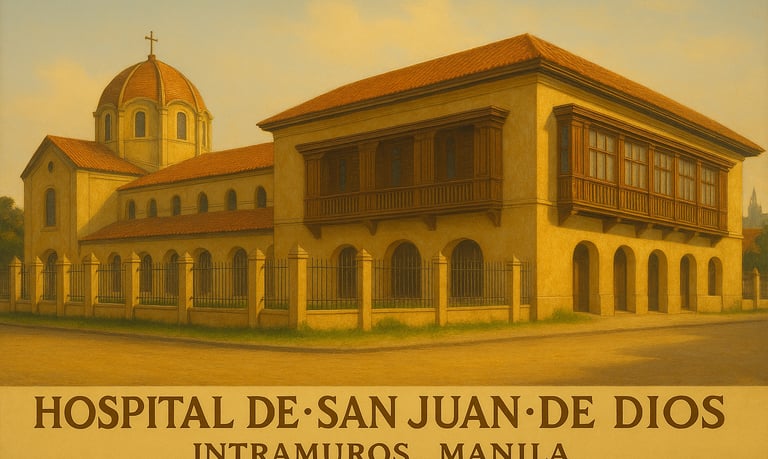

The Order of Hospitallers—known in 16th-century Mexico as the Juaninos—first arrived in Manila in the early 1600s, bearing a mission of mercy. Yet their initial efforts were met with resistance and the absence of a Royal Order, forcing them to withdraw. Decades later, in the mid-17th century, they returned with renewed resolve. This time, they succeeded—granted a Spanish royal decree and colonial endorsement to assume stewardship of the troubled Royal Hospital of Manila, then known as the Hospital de Naturales de Manila.

Renaming it Hospital de San Juan de Dios de Manila, the Brothers honored their founder and patron, St. John of God—protector of the sick and champion of the poor. From the mid-1600s to the late 19th century, they faithfully managed and operated the hospital, transforming it into a center of compassionate care. Their legacy was built not only on healing, but on dignity: serving the afflicted, the wounded, and the abandoned with European-style medical rigor and deeply human hospitality.

The Hospitallers were pioneers of modern hospital practice in the Philippines. They introduced systematic order, cleanliness, and—most notably—the professionalization of nursing care. Their ranks included locally recruited members, among them Bro. Apolinario de la Cruz (Hermano Pule), a donato whose life would later contribute to ignite the flame of Filipino national consciousness.

After nearly two centuries of service, the Order returned to Manila in the post-EDSA era, continuing their mission of mercy. Today, they remain faithful to their charism of hospitality—offering shelter to pilgrims and travelers, raising abandoned children, and caring for the sick and wounded. Their enduring presence is a living testament to love that heals, welcomes, and restores.

AI-enhanced Image of the San Juan de Dios Hospital built by the Hospitaller Brothers

AI-enhanced Image of the Hospitaller Brothers

AI-enhanced Image of the Hospitaller Brothers

AI-enhanced Image of St. John of God

The Daughters of Charity, Servants of the Poor:

A Legacy of Mercy and Compassion

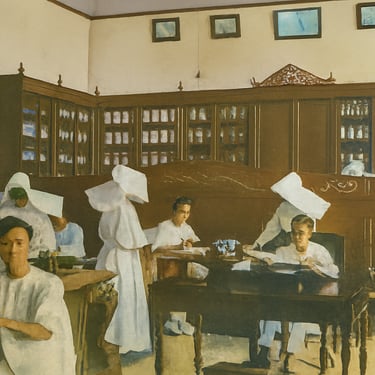

St. Vincent de Paul, together with St. Louise de Marillac, founded the Daughters of Charity in 1633 and called them “Daughters of Charity, Servants of the Poor.” Unlike traditional religious orders bound by cloister, he envisioned them as women whose convent would be the houses of the sick, whose cloister would be the streets of the city, and whose mission was to serve Christ in persons who are poor, sick, and abandoned. From France, their mission spread across Europe, and by the mid-19th century the Hijas de la Caridad—well established and recognized for their charitable works in Spain—were entrusted by Queen Isabella II with a new mission in the Philippines. Through her royal decree, they arrived in Manila to revitalize charitable institutions and assumed stewardship of the Hospital de San Juan de Dios, continuing the legacy of St. John of God with Vincentian heart and hands.

Formed in the missionary tradition of service to the poor, the Daughters became part of a broader reform in ecclesial and social outreach across the islands. They inherited a quake-damaged facility in Intramuros and, with quiet resolve, rebuilt it destruction after destruction—preserving its name and sanctity while relocating it from Intramuros to Pasay, and transforming it into an integrated credible hospital in the 20th century.

Known for their Christocentric, hands-on approach to care, the Daughters embodied the seven corporal and seven spiritual works of mercy. Their service was not merely clinical—it was deeply personal, rooted in the dignity of each soul they encountered.

Through every chapter of Philippine history—from the waning years of Spanish colonization, the Malolos Republic, American occupation, Japanese wartime devastation, post-war independence, the EDSA Revolution, and into the digital age—the Daughters of Charity remained steadfast. In times of upheaval and renewal, they shepherded the institution with grace and hope, guiding it into what is now known as San Juan de Dios Educational Foundation, Inc. (SJDEFI).

Having weathered the global trials of the COVID-19 pandemic, SJDEFI continues to bear the Vincentian legacy in a world shaped by disruption, digital transformation, and AI-enabled care. It stands today not only as a center of healing and learning, but as a living testament to enduring love—faithful to its mission, resilient in its witness, and ever attuned to the needs of the times.

Serving Genuinely in Charity

AI-enhanced Image of Daughters of Charity who took over the hospital.

AI-enhanced Image of the San Juan de Dios Hospital built by the DC.

AI-enhanced Images of the hospital in over 100 years under the Daughters of Charity

Time and Again, Legacy Tested

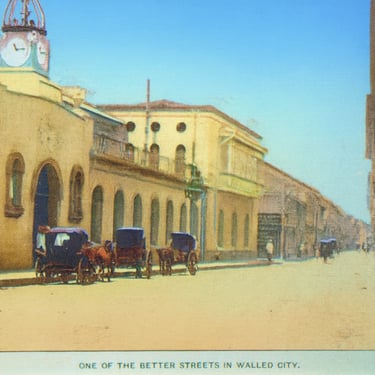

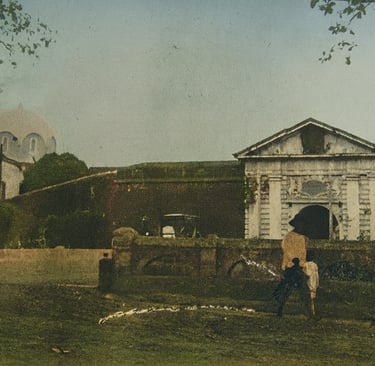

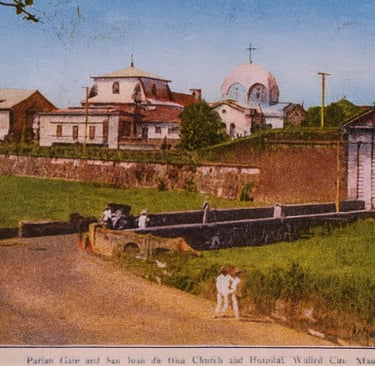

In the early 20th century, Intramuros stood in serene dignity—its cobbled streets cradling the quiet rhythm of normalcy and secured confidence. Within its historic walls, San Juan de Dios Hospital, the Daughters' house and chapel once stood firm.

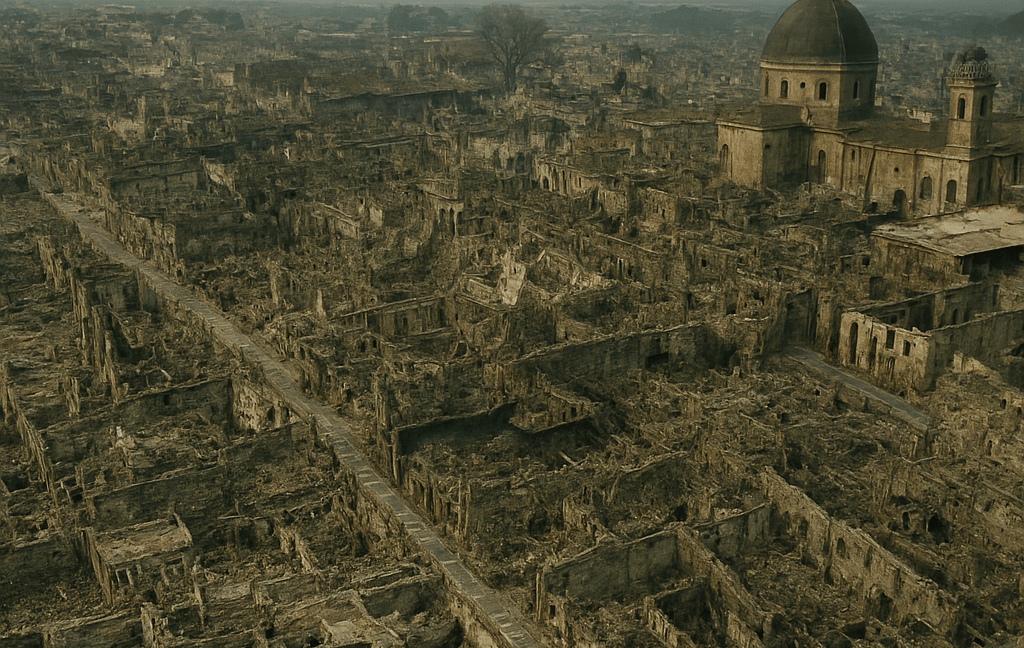

But in 1942, as the Japanese Imperial Army occupied Manila, that peace was shattered. The hospital was seized, marking the beginning of three harrowing years of hardship and sacrifice. Those dark period of our history tested the spirit of courage and compassion for victims and oppressors alike.

Remember

the Battle of Manila

"Manila was the second most destroyed city — next to Warsaw — after World War II. It seems with each year that passes, the physical scars remain, but the memory of what happened here diminishes. Thankfully, there are individuals who are doing everything in their power to make sure the memories of what happened in Manila during World War II are not forgotten. . .

"From February 3 to March 3, 1945 the Battle for Manila raged. It is regarded as some of the worst urban fighting during World War II in the Pacific, with around 100,000 civilian casualties on top of combatant losses. Every atrocity imaginable, and many unimaginable, happened." - Alejandro R. Roces

Much of the graceful city was turned to rubble. Large parts of its rich cultural heritage — archives of the Spanish colonial era, records from the Philippine revolution, birth and death certificates, ornate churches, grand libraries and treasured art — were obliterated. Only Warsaw suffered more among Allied capitals in the war.

“We had our own holocaust here,” Mike Alcazaren, a Philippine documentary maker who attended the Feb. 18 ceremony, told me. “And no one knows about it. It’s very sad.”

Yet I knew almost nothing about the monthlong battle that had devastated the heart of the American colony. History books barely mentioned it. Schools didn’t teach it. Monuments didn’t honor it. I wanted to find out why.

Manila was ravaged in WWII.

Why do few remember the suffering and sacrifice?

"Feb. 23 — Early in the morning we greeted each other for having passed a better night. As soon as possible, we said our morning prayers. Just as we had concluded, as if by one switch – cannons, bombs, dynamites, hand grenades, and machine guns – all were suddenly ferociously at work. Faces paled, nerves wrecked and all sought for shelter. As usual, Sister Melecia and I remained. Quite carefree, I went for some trifle from a basket, while she began to prepare our breakfast of some weak coffee. Presently, wall fragments and heaps of dust fell over us that made me hide among our baggage and Sister Melecia ran close to me. We prayed, but only to be interrupted by the thunderbolt sounds, quakes, bullets, and shrapnel in all directions. Rain of dust fell over us anew.

Conscious of the real and direct attacks and of our danger, Sister Melecia said, “Ah! We can no longer stay here; let’s go down,” and down we fled. But in passing by our usual place, I was reminded of our old house maid. I had hoped she was with the rest, but no, glancing back, I saw her all alone trying to fix herself. How could she be left as such? I decided to take her with me. I ran back just in time to lift her up, as she had rolled to the ground. Being too weak to walk, to take her downstairs was impossible for me. All I could do was to place her against the wall and stay with her, and together, we began to pray.

I was kneeling for scarcely ten minutes, when I felt something fell down on my left foot,- something heavy, warm, and grasping. Was it only some stone? I stood up and saw my foot profusely bleeding, skin and flesh grabbed away, characteristic effect of the shrapnel. My first impulse was to run down for dressing, but it was too risky, so I had to resume my place resignedly.

Terror and panic were in everybody’s heart and soul produced by these deathly instruments of war. The trying days and nights seemed to have reached their doom. We resumed our prayers, and from all corners nothing could be heard but prayers, ejaculations, and petitions accompanied by sighs, weeping, and lamentations, blending with the horrible sounds of the death strokes from outside."

A Legacy of Courage

"We were only two in our corner, but from time to time a woman, a child, or a girl would run to the spot until a group was formed. Copious rain of earth fragments and suffocating dust fell unpityingly over us, thus falling upon my bleeding wound, - but worse than these, I was convinced that bullets and shrapnel were falling everywhere because it seemed that in every wave of shots, a woman, a child, or a girl fell victim to it – dying or in agonizing pain. In such a crisis my weakness gave way and could only repeat as a prayer, “Oh, please, enough . . .”

Then another panic. A stream of water flowed in the room, taking us by surprise, as we were in the days of dryness. From where it came, we knew not and it came with such rapidity as to fill our place in just a few moments. Oh, how dreadful it looked, and more so when the dead and the suffering began to float over, just upon my feet and before my eyes. “Is this an inundation? Some strategy of the Japs to finish with us all?

With these thoughts I could only close my eyes, fearing that my end was coming, too. After having been invoking the Blessed Trinity, our Blessed Mother, and the Angels and Saints and the Holy Souls, I could only keep repeating these, “Oh, my God, I beg Thee pardon for all; I give Thee infinite thanks for all. I ask pardon for all my sins and for those of the whole world as the immediate cause of this war and its cruel lashes; and infinite thanks for all our sufferings as its consequences.

I got soaked up to the legs and, poor wound! It had already its first dressing of dust and dirty water. That no infection occurred can only be attributed to God’s special mercy and grace. I managed to get closer to my old maid where the ground was more elevated, and waited for God’s will."

In the weeks of February 1945, inside the walls of Intramuros, the San Juan de Dios Hospital, run by the Daughters of Charity, was caught up in the thick of battle between the Japanese forces still occupying Manila and the invading American forces.

The account of Sor Consuelo S., D.C. provides a unique and firsthand description of the events in Intramuros during the Battle of Manila in the period of February 3–26, 1945. Harrowing in its details, the account testifies to the courage and faith of the DC Sisters and the people who were with them during the ordeal.

Harrowing War

The Last Days of San Juan de Dios Hospital in Intramuros

We were not spared from the destruction of Intramuros in 1945 during the Battle of Manila.

AI-enhanced Images of the Intramuros where San Juan de Dios Hospital and Chapel once stood.

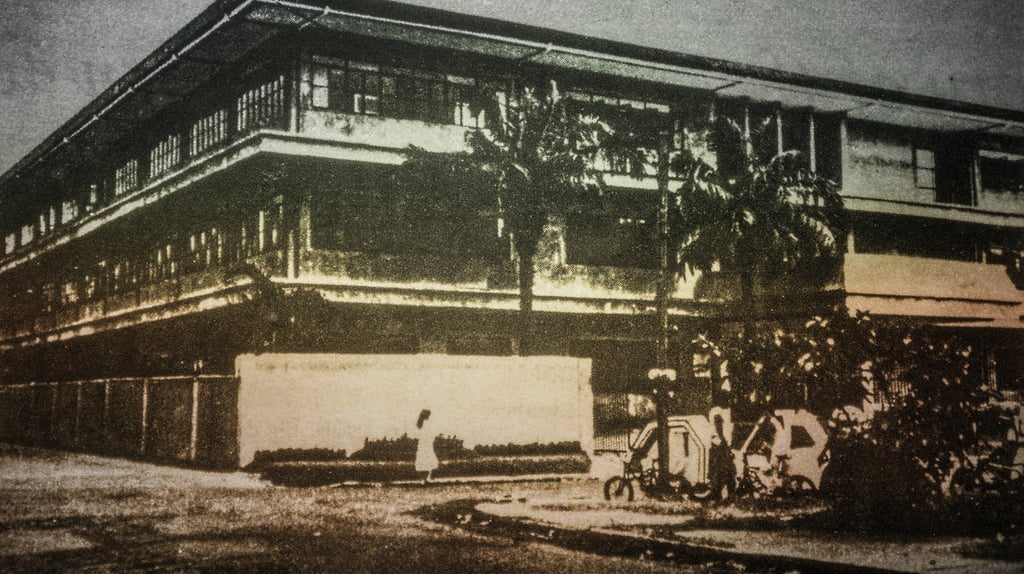

Fernando Amorsolo's Narrates on His Canvass the Rise and Reborn of the New Facility

San Juan De Dios College

San Juan De Dios Hospital and College